You’ll find that—despite their strange names—these principles are easy to understand. You’ll find out why MosaLingua works and how it differs from other methods. In fact, we’ve already helped over 500,000 people learn languages!

The Spaced Repetition System

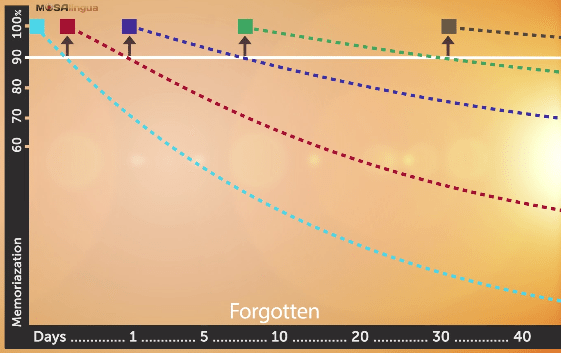

Everyone knows that the more you review a concept, the more likely you are to remember it later. On the other hand, few people know the best way to perform these review sessions. The least effective way to learn is to review the same word 10 times right before a test because you’ll forget the information only a few days later. In order to commit the information to your long-term memory, you need to space out your review sessions. The review schedule will differ for each person and each concept to be memorized. For example, learn a word for the first time, then review it 5 minutes later, then again 7 hours later, then 3 days later, then 10 days later, then 1 month later, until the word has been stored in your long-term memory. This schedule is based on the forgetting curve—spacing your review sessions apart so that you review information just before you are likely to forget it (ref. Bahrick & Phelps).

The SRS curve: Note that at each spaced review session, it takes increasingly more time for you to forget the information.

MosaLingua uses a slightly modified version of Piotr Wozniak’s research-based algorithm. If you would like to learn more, please read our article on MosaLingua’s Spaced Repetition System.

Active recall

Multiple choice questions or other learning systems that require learners simply to recognize the correct answer from a list of possible answers are not at all effective for memorization.

To really learn something, you need to be able to extract it easily from your memory, without assistance or a clue. This is especially true for learning a new language.

MosaLingua uses a system of flashcards that requires more effort but is much more effective.

Additionally, the act of regularly extracting information from your memory reinforces your memorization (ref. Pashler et al, 2007). To put it simply, the route through your neurological network that allows you to access the information becomes faster and more reliable.

But that’s not all: recalling a foreign-language word or phrase by drawing from deep within your memory, trying to pronounce it well, then turning the card over to see the correct response right away is not only effective but also incredibly fun. That’s why millions of people use flashcards when they’re learning something new.

Metacognition

The simple act of thinking of an answer then revealing it would be incomplete without the third and very important component of this learning system: metacognition. This is the act of reflecting on your own thoughts. Before revealing the answer, MosaLingua asks you to evaluate your memorizations (on a scale of 1 to 4). Research has shown that evaluating your own learning is highly effective for reinforcing your memory (ref. self-assessment, Sadler, 2006).

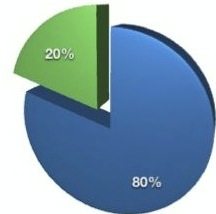

The Pareto principle

The Pareto principle explains that 80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes. This applies to almost every domain and is especially true for languages:

Did you know that the 100 most common words in English account for half of the written corpus?

Evidently, you shouldn’t quit after learning only 100 words. Instead, you should concentrate on the most frequently used words and you’ll make spectacular progress. What’s more, globish (global English) has shown that it’s possible to express yourself using only 1500 well-chosen words (which would take less than 3 months with only 10 minutes per day with MosaLingua). Once you’ve acquired this base, MosaLingua proposes specialized vocabulary suited to your needs (the application has over 3000 words).

The same principle applies to grammar. MosaLingua introduces phrases gradually with simple structures that apply to most cases (sentence patterns: always the 20% that apply 80% of the time). Once you’ve memorized these simple phrases, your brain extracts models and adapts them to other situations. Therefore, you can express yourself well without learning all the grammar rules and their exceptions. Instead, learning grammar right away can actually slow the learning process and the fluency of your speech. (You don’t have time to think of grammar rules when you’re speaking!)

Furthermore, when you know that what you’re learning is useful, memorization is much easier. You’ll never have to learn useless phrases with MosaLingua (e.g. “My tailor is rich”); instead, MosaLingua will recommend words or phrases from the list of the most used words or phrases based on your level and specific needs. However, you are in charge of your own learning: you’ll always have the option to skip over a word or an exercise if you feel that you don’t need to learn it right away.

Learner motivation and psychology

Learning a language is a fantastic experience, but it requires considerable effort and numerous changes in the way you think and the way your brain works. For example, scientists have shown that people who have mastered at least two languages have a different electroencephalography (EEG) than people who only know one language (ref. Klein et al. 2013). Knowing more than one language also helps prevent the onset of Alzheimer’s disease (ref. Alladi, et al. 2013).

Furthermore, the number one cause of failing to learn a language is giving up. People become tempted to give up as a result of poorly managing their motivation (which varies with time). However, there are ways to overcome your lack of motivation and transform work into an enjoyable habit.

Moreover, a number of people—unbeknownst to them—have roadblocks for some foreign languages (often formed during their education) and will have to do away with all their false ideas about language learning.

These changes can’t all be made in one day and need to be worked on throughout the learning process. We know that everyone is different, and therefore everyone has different methods of learning. In fact, the MosaLingua team is made up of many experienced language teachers and each of us have learned between 2 and 6 languages (through self-learning).

That’s why we offer free learning help via email, presenting the Web’s best resources, as well as tips through bonus material or the learning community on the MosaLingua blog. We’ll give you all the tools you need to develop your own personalized learning method that is adapted to your needs.

The MOSALearning® method

The combination of these 6 concepts forms the MOSALearning method (Motivating Optimized System for Adaptive Learning) created by MosaLingua. This method is constantly evolving as we aim to apply the latest research discoveries to create a state-of-the-art method that is highly effective AND easy to use.

References:

- Bahrick, H. P., & Phelps, E. (1987).

Retention of Spanish vocabulary over 8 years. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. - Pashler, H., Bain, P., Bottge, B., Graesser, A., Koedinger, K., McDaniel, M., & Metcalfe, J. (2007).

Organizing instruction and study to improve student learning. Institute for Educational Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. - Sadler, P. (2006).

The impact of self- and peer-grading on student learning. Educational Assessment. - Denise Klein, Kelvin Mok, Jen-Kai Chen, Kate E. Watkins. (2013).

Age of language learning shapes brain structure: A cortical thickness study of bilingual and monolingual individuals. Brain and Language. - S. Alladi, et al. (Nov. 6, 2013).

Bilingualism delays age at onset of dementia, independent of education and immigration status. Neurology.

Image by: Patrick Hoesly